New and unexpected risks become increasingly challenging as we move on in life. That’s partly because we have already invested heavily in coping with the risks we encountered earlier on.

Risk management has become an important part of everyday modern life. This responsibility weighs heavy on us. The more since it covers so many topics, such as physical, emotional, and social risks.

To avoid responsibility and self-reflection is the worst strategy anyone can take if challenged by new and unexpected risks. The best way to charge these risks is head-on, but with as much care as possible.

Some of the links might be affiliate links. As an affiliate associate, we earn a small commission when you purchase any of the products offered through the shared links at no extra cost for you. This helps us to maintain this website.

Table of contents

Path dependency

This so-called path dependency makes us less resilient to new and unexpected risks. Growing old is an excellent example of such a new, albeit hardly unexpected, challenge. Ageing is something we all hope for and at the same time is totally unavoidable.

Of late some debate originated on how we perceive the new and unexpected risks. The most important observation is that we tend to avoid confrontation with these risks. We also tend to burden others with the handling of these risks. We tend to avoid responsibility and stop all critical self-reflection: ‘New and unexpected? Please not in my backyard!’

Take new and unexpected risks head-on, but with care

There are many interesting guiding principles if it comes to age with care, but for now, I will challenge three: physical integrity, emotional awareness, and social integration.

1. Physical integrity and new and unexpected risks

We protect our physical integrity with such things as clothes, a house, hygienic provisions, and safe foods. In fact, the list of these protective provisions is endless.

From sewage structures to academic hospitals and from highly complicated legal systems to expiration dates on food packages.

But despite all these provisions and almost total control over our physical integrity, we still feel highly vulnerable. This might be because we have no control over the many systems and structures that safeguard us.

What remains is our trust in those who are responsible for these systems and structures.

Lack of trust

As it appears, it’s indeed our lack of trust in those responsible that makes us feel vulnerable. This lack of trust usually emanates from the tireless and never-ending discussions about those very few things that go wrong. We don’t want anything to go wrong.

Although the aim as such, to prevent anything to go wrong, is valuable, it’s an aim we cannot afford. That’s why it’s far more valuable if we look at our own behaviour and wonder what we can do ourselves to improve the way we handle new and unexpected risks.

Related: 11 Simple Steps to Change your Life no Matter what Age you are

Do you just drive around or do you consciously participate?

Let’s take an old and well-known risk of everyday life as an example: the way people drive around on the roads in their cars.

For starters, that is just what most people do: they drive around in their cars. They do not participate in traffic. They’re alone on the road and everybody else has to take them into account.

There are three reasons relatively few people get hurt in accidents. People don’t want their cars to be damaged. The passive safety of cars is these days at an exceptionally high level. And third, there are just enough people that do feel responsible. They anticipate what others do, abide as much as possible by the traffic rules, plan their trip, and use their car where it’s made for.

Rules of thumb

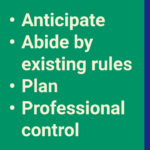

Anticipate, abide by existing rules, plan, and some professional control are rules of thumb that anyone can practice if encountered with new and unexpected risks. I have designed an exercise to challenge you to pick up this type of behaviour.

Try to invent three rules that you think other car drivers would appreciate you would abide by, apart from the obvious traffic laws. Please let me know what you came up with.

2. Emotional awareness and new and unexpected risks

A good friend of mine once stated that rationality is a desperate and impossible way to control our emotions. I completely agree. The previous subject of traffic behaviour is a fine example of how my emotions can get totally out of control. When I think somebody tries to do me wrong on the road I can flip out. Fortunately, this only happens now and again and I work hard to try and keep total control over my road rage.

Control precedence

Yet this example clarifies one of the most important emotional rules: emotions have ‘control precedence’. No matter what we try, or what we do, if passionate enough our emotions take over total control. As far as I’m concerned this happens far more often than we are aware of or like to admit.

Lex talionis

If faced with new and unexpected risks our emotions can hamper our ability to try and practice the four rules of thumb mentioned earlier.

One good example is the ‘lex talionis’. Our need for revenge originates from the damage we think is done to our feeling of self-esteem. Power inequality, loss of status, and loss of self-esteem all contribute to our need for revenge.

But the reasons for our need for revenge are probably more profound: revenge probably originates from the damage to our elementary feeling of personal value and identity.

Self-determination, in the sense that we are able to decide for ourselves what we do and don’t do (including the feelings we do and don’t want to experience), is the ground on which our sense of self-determination rests.

Is there a need to keep your emotions in check?

Perhaps there is another lesson here. If we are confronted with new and unexpected risks, will the four rules of thumb (anticipate, abide by existing rules, plan, and professional control) be able to keep our emotions in check? Please let me know how you experience this.

3. Social integration and new and unexpected risks

The ‘lex talionis’, the law of revenge, teaches us that social life comes with hefty risks. On the other hand, the ‘law of the conservation of emotional momentum’ gives us the idea that love will last forever. Social life offers us ambivalent opportunities.

Are we in control or being controlled?

From one moment to the other the love we cherish for someone can be hampered by new and unexpected risks. Such as a sudden and unexpected illness of a parent. When these risks materialize, strong emotions will elicit. As much as we think to control our social life, at such moments it most certainly is the other way around. But how to maintain an equilibrium between ‘in control’ and ‘being controlled’?

Social relations have a functional, normative and expressive dimension. Social relations are functional if they alleviate stress and contribute to a quick recovery and the feeling of trust and safety. The normative dimension refers to the duty to contribute to public interests and to care for yourself and others.

Modern societies stress values such as personal development, personal identity, equality, responsibility, independence, self-realization, and control.

These personal, expressive dimensions dominate the functional and normative dimensions. As a consequence public interests and the care for others receive less attention in modern social life.

To counter the lack of interest in the functional and normative dimensions of social integration and to maintain a decent social life at the desired level is one of the biggest and most rewarding challenges we face. We need to balance the three dimensions of social life. Again it’s the question of whether the four rules of thumb fit when new and unexpected social risks are encountered.

Would you be willing to share with us your experiences at this point in your social life? Share it in the comment box below.